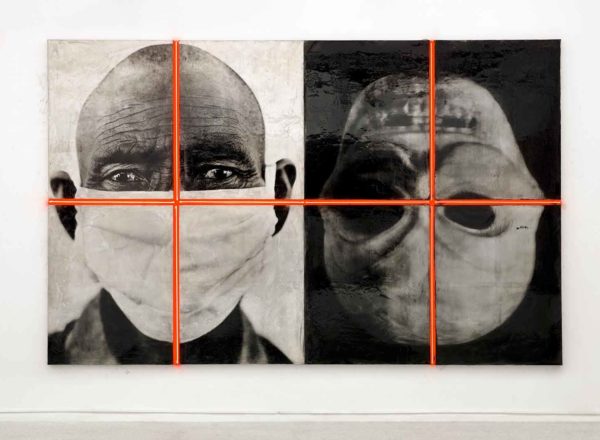

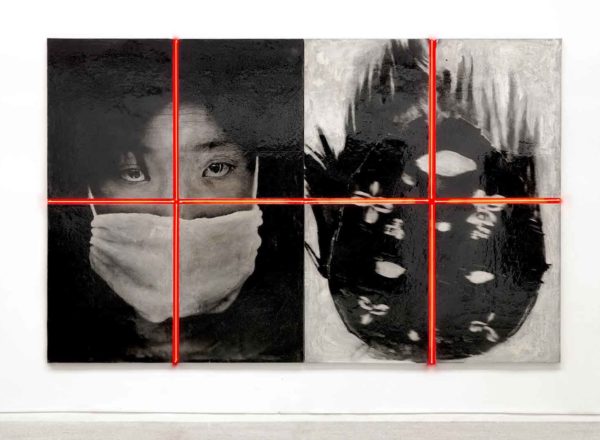

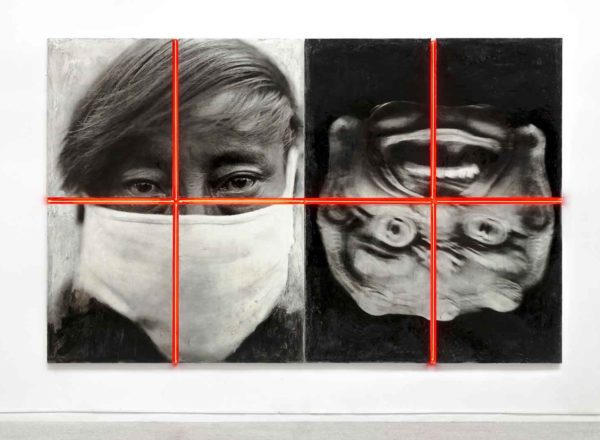

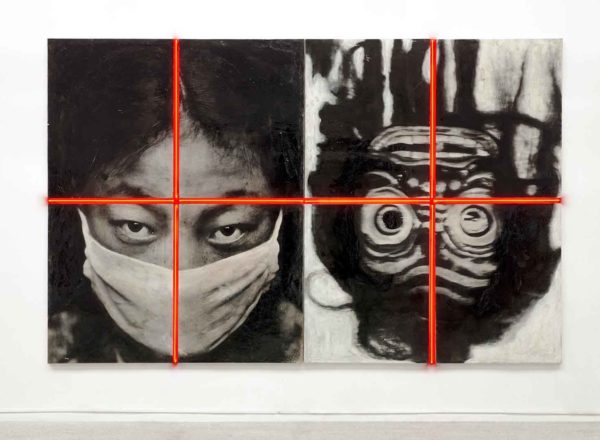

In his recent works Gao Bo makes visible the passage of time in his works, reworking his first photos until they are erased and disappear. Offering of the Mandala goes back to the “duality portraits” made in Tibet in the 1990s, this time using an entirely new updated piece performed each time the work is exhibited. Presented in the form of double quadriptychs bearing red neon crosses, the photographs are first coated in resin, then covered in black and white paint, which is finally partly removed. The original image moves from a state of presence to one of complete disappearance before partly reappearing, a memory or ghost of the initial work, thanks to the successive interventions of the artist. Gao Bo carries out his work on the frontiers of disappearance so as to reveal the truth of the artwork more effectively. Moving beyond the binary separation between presence and absence by using his own dialectic, the artist’s work is an experimentation that has the character of a revelation. Gao Bo extends this work in a performance where, having painted the works, the bodies of the artist and his partner crash into one another, roll on the ground, undress, and disappear under the same paint, removing the frontiers between the artist’s body and his work, between man and woman, and between black and white. Facing these works, Gao Bo has made 1,000 prints of Tibetan portraits on pebbles, each bearing a reference number from 0001 to 1000. A tribute to the “marniy stones”, votive objects used in Tibetan Buddhism, this installation was designed as an offering made to the Tibetan people the artist loves. But behind the profound unity of these 1,000 anonymous faces, it’s their fragility that soon strikes the viewer. The fragility of these makeshift, experimental prints on pebbles that seem destined to disappear, scattered, trampled on, forgotten. The strength of Gao Bo’s work lies in this contrast: on the one hand, the fragility of faces and the accumulation of bodies; on the other, the implacable creative and experimental vitality of the artist attempting to capture, pehaps for an instant, the richness and power of life.

“… Art is memory work.. Indeed in another work, ‘ 献曼达’(2009) we see a collection of stones, each with a face (echoing the memorializing works of Boltanski); we witness the superimposition of an image upon a stone for the remembrance of a life; ’head stones’ in the graveyard of memory. Found Objects and the Still Life in this sense are religious ‘fetishes’ —with the word ‘fetish’ used in the proper sense of the word, as something, precious, profound, sacred, so to be protected, remembered (and not as used in its Enlightenment-rationalist, or intellectual neo-colonialist, form as a put-down, or negative comparative, for the religious —non-rational— beliefs and practices of other social forms; whilst remaining blind to the beliefs implicit in modern forms of identity, or denouncing all non-rational elements of human culture). If the celebratory end or appropriation of cultural objects offers a cultural landscape as collage as collection, as fragmented modern experience as positive, as pleasure, as jouissance, then the more thoughtful end of this appropriation, through its lyricism, points to something absent or lost, conjures up other modalities of reflection and feeling, pointing to a ritual of ‘remembering’; remembering what is important… asserting an identity focused upon reflection and value (also reflexivity and value, with the paradoxes of ironic self-consciousness and the necessary performative assertion of value(s)). Performing a quest (ritually, as art only can): searching for (and in so doing, creating) meaning (as humans only can).” Wondering in the Land of the Lost

(The Art of Critical Landscape).

Dr. Peter Nesteruk, 2016