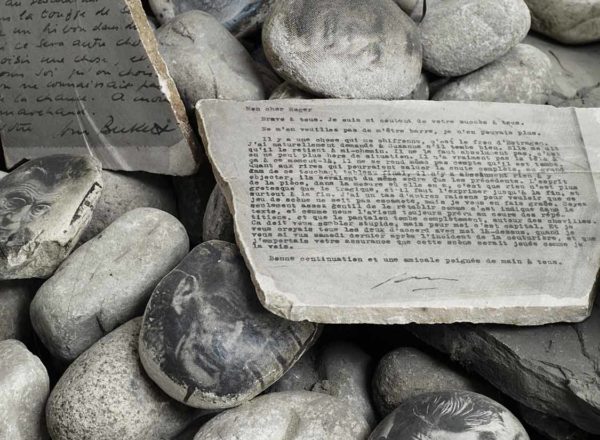

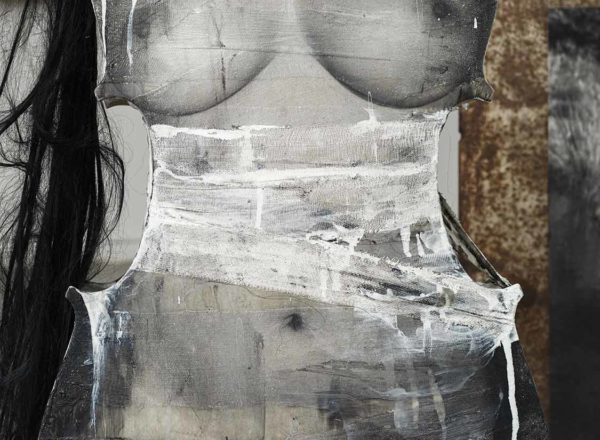

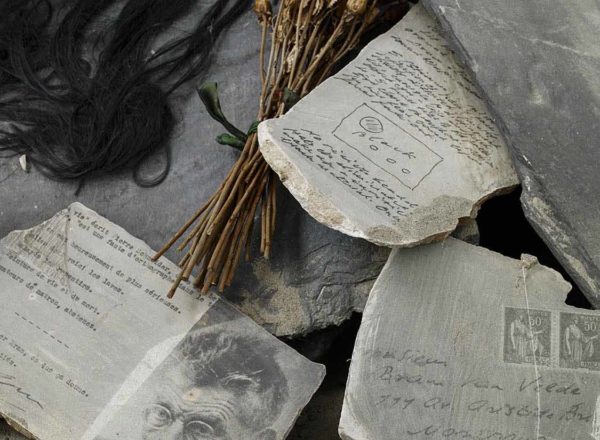

Silver bromide emulsion print, anonymous photo of Samuel Beckett printed and stuck onto a salvaged metal floor. Rock from a river, curiously broken stone slabs and readymade cello wrapped in medical bandage, artificial hair, two anchors and two small old wooden boats found at antique fairs, neon text.

In the beginning, there was that anonymous photo of Samuel Beckett facing the photographer, crossing what looks like a little stream in a small boat reminiscent of a floating coffin. Some time later, Gao Bo bought a series of twenty or so small boats from a Chinese antique dealer, as well as several anchors, with the feeling that there was a connection between these objects and the anonymous photo of Beckett. When, still later, he re-read Waiting for Godot, the last words and final stage direction of the play:

– Well, shall we go?

– Yes, let’s go!

They do not move

Echoing the photograph, triggered the creation of the installation entitled Beckett – Faramita Laostist. Designed as a mausoleum to Beckett’s memory, the work combines the abovementioned photograph, some boats and anchors, stone slabs printed with portraits and excerpts from the writer’s archive, a cello representing the body of a woman, and two neon signs saying ‘the other shore”. While paying tribute to one of his masters, Gao Bo explores the theme of death, seen as an endless crossing from one “shore” of life to another, a perpetual movement alternating creation and destruction. In the centre of the work, the figure of the wounded muse, symbolised by a cello wrapped in gauze strips, reflects the creative process of the artist during what he calls his “black period”: through his works Gao Bo confronts death as a survival strategy and a way of being reborn.

« Abode where lost bodies roam each searching for its lost one. »

Samuel Beckett, The Lost Ones

« In, ‘Beckett – Faramita Laostist 裸思者的彼岸’ (2010) we experience Beckett as ‘Beckett’; the Proper Name as a cultural referent which includes the impact of his works, as a lost self as existential uniqueness and isolation, existential ‘thrownness’, as well as dilemmas of moral choice in a post-foundational world: asking the question: whence value, whence morality? Unfounded but necessary. Inferred in art. (Since Romanticism offering art as a source, or interpretation, of value in the world – at once symptom and diagnosis; an alternative source of the sacred). A ‘thrownness’ applicable collectively to ourselves as a species (as in Beckett’s short prose work, ‘The Lost Ones’). We have found ourselves as lost; are ready therefore to found ourselves anew, to reinvent values – to discover (to assert) values where we no longer can support beliefs…”

Dr. Peter Nesteruk, 2016